Astralbrowser: designing an incredibly fast but niche file search engine

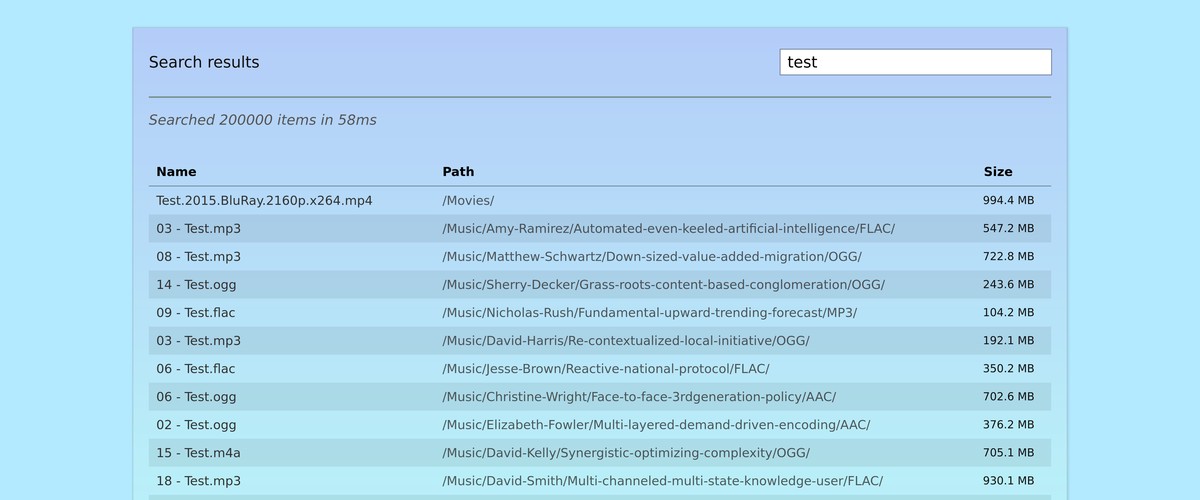

This post covers the background and design of Astralbrowser – a simple, fast file search engine I created. Here’s a demo of the final implementation in action:

I have a lot of files, dating back over about 25 years. I also have a shared collection with some friends – around 200,000 files in total.

I needed a way of hosting the files for quick access over a network, as well as a quick file path only search feature.

Looking around, there were a few options but most were either heavyweight or unsuitable:

- Nextcloud – cumbersome and complex, does much more than browse files

- Seafile – more or less the same problem

- Nginx autoindex in HTML mode – too limited. Can be styled, but no search.

- Filebrowser.org – Seems pretty good! However, search is for the current directory only.

- Caddy file browser – Slick but same problem.

That’s not to say those are bad – all engineering is a compromise. All good engineering is choosing the right compromise!1

I made a simple file browser using Svelte which builds upon the nginx autoindex configured for JSON output. This was convenient and lightweight – it worked well.

I then extended it to have a search functionality with an interesting trade-off; the way it works is a trade-off – speed over efficiency and accuracy.

Check out the demo and source code if you like!

My favorite example of great design and manufacturing, but terrible engineering (and market fit!): The Juicero ↩︎

Background

A naive approach to file searching is to crawl the entire filesystem on each search, matching the query against the file paths. This works, but is generally slow and not scalable due to the overhead of filesystem access; if you’re using a mechanical hard drive, you’re waiting for a physical read head.

Therefore, most search engines build an index where the expensive crawling is done beforehand to allow much faster searches later. The downside is possibly outdated results.

To make the system appear even faster, techniques like incremental search are employed, where results are shown as the user types, updating in real-time. This of course depends on being able to search faster than the user can type to make it seem instantaneous.2

Some filesystem search engines do a lot more than what I need. For instance, Google drive, Onedrive and Windows explorer index the contents of files as well as the path information. This requires a much larger index, and more complexity too. Generally speaking when I search for a file, I know roughly what it’s called so I don’t find myself needing a content search at all.

I find it annoying where this is used with a slow backend. It can make the interface seem much more laggy then traditional search, particularly if results are not invalidated properly or the system is playing catch-up with itself. Jellyfin, I’m looking at you. ↩︎

The idea

I wanted to keep the approach light – I didn’t want to run a database server or even a server backend for that matter. I like the idea of a static site, so what if I could do the searching ensrely in the browser?

To see if this was feasible, I did some rough calculations. I used the find command to make a basic list of all files:

find /path/to/files -type f > index.txt

This produced a list of all file paths, one per line weighing in at about 19MB for 200,000-ish files. Given there are a lot of repeated path components, this file can compress really well – using gzip, it shrinks down to about 3.5MB – over a 5x improvement! This is significant as browsers and webservers can be configured to handle gzip compression transparently.

3.5MB is a relatively small file to download nowadays. It’s about the same size as a single image. What’s more – if I could figure out a way of streaming the file to provide search results in real time, I could make the system respond much faster on average as there would be no need to wait for the entire file to download before starting the search.

Of course, I could use some kind of tree structure to reduce the repetition in the index, but that would add complexity and also make streaming more difficult. Besides, the whole filepath is important context when it comes to matching. Gzipping the index takes care of the repetition quite well anyway.

Indexer

Let’s start with the indexer. Initially I wrote the system to use exactly the find based index described above! That worked great but I wanted to be able to display the file size as well as the total index and filesystem size without downloading the entire index.

As a result I created a simple index file format, optimised for streaming. Here’s the format:

<number of files> <total size in bytes> <timestamp>

<filepath 1> <size in bytes>

<filepath 2> <size in bytes>

...

Given the streaming approach I wanted to use, the information first line (the header) is available immediately to the search engine. This way we can show search progress, and check that the index isn’t too old or empty.

Here’s the core algorithm I used to create the index written in python, available in astralbot-indexer:

| |

It’s just a basic filesystem crawler based on os.walk(), gathering some metadata with os.stat().

There a are a few optimisations in there – we sort by file size, as larger files are more likely to be relevant to the user (me and my friends in this case).

Note that if I sort instead by filepath, the index may compress better as gzipping via nginx happens in chunks – the more similarities in a chunk, the better the compression.

To reduce the filesize further, I made sure the indexer ignores certain files and directories. MacOS, for instance, will litter the filesystem with .DS_Store files which are used for thumbnails and metadata. These are not useful to index, so we can ignore them. The best example is version control directories like .git – these can contain thousands of files which are not relevant to the user.

I also don’t match files under a certain size (like 1KB) as these are likely to be placeholders or empty files.3

As for gzip compression, we can handle this transparently as mentioned above with the right directives in the nginx configuration:

gzip on;

gzip_types application/json text/plain;

Note that using .txt as the file extension is important here, so nginx will match it as text/plain – and therefore gzip it – providing you have mimetypes configured correctly.

I chose the filename .index.txt for the index file – so nginx compresses it and also so it’s hidden by default on linux systems when the root directory is listed.

When using the indexer, I recommend running it hourly or daily via cron or systemd. Systemd is better, as failures are easier to observe and logs are available by default. I included some systemd configuration4 examples in the repository, as well as a script to set them up: install-indexer-example.sh.

Client stack

I chose Svelte as it has no runtime component – making the final bundle small and suitable for inline deployment;5 it is also composible, mixing in HTML/CSS and JS into a single file per component.

I also chose Typescript for type safety – with static typing, you can say goodbye to an entire class of bugs.

Everything else I did myself as I don’t want any heavy libraries or a big dependency tree.

Not with the demo, though. ↩︎

File browser

It is possible to style the default HTML output of nginx autoindex, but what you can do with the output is limited.

Nginx also has a JSON autoindex mode – it produces a list of objects like this:

[

{

"mtime": "Tue, 20 Sep 2022 17:51:11 GMT",

"name": "test directory",

"type": "directory"

},

{

"mtime": "Fri, 01 Apr 2022 22:37:46 GMT",

"name": "test.mp4",

"size": 68580918,

"type": "file"

}

]

The code to render this in Svelte is straightforward – see /src/LsDir.svelte. As such, I won’t cover it here.

Do note, however, that for large directories (1000s of files), there is a noticeable delay while the JSON downloads and is parsed. For the latter part the progress bar animation is blocked!

There’s no reason why LsDir.svelte couldn’t be adjusted to stream the JSON much like the process described below for the search index file.6 That would mean no perceptible delay for large directories vs smaller ones.

Something to make a pull request for if myself or someone hasn’t already! ↩︎

Index streaming system

After proving the concept with find I got to implementation. See searchengine.ts for the full code – I’ll cover the key parts here.

Chunks and re-assembly

In order to stream the index file, we need a way of receiving chunks of the index data bit by bit. The ReadableStream: getReader() is supported is most modern browsers as part of the Fetch API – it allows just this.

There is no telling how big each chunk will be – it depends on a plethora of hardware and software between the server and client. Each chunk may contain full entries but also fragments of the last and next entry. For instance:

Chunk n:

/Xbox-Series-X/Digital/Vision-oriented-background-capacity (2008).iso

178528016 ./Music/Kayla-Rodriguez/Seamless-intermediate-productivity/MP3/13 - Laugh.ogg

708481940 ./Games/Switch/ISO/Op

Chunk n+1:

en-architected-interactive-matrices (2019).zip

6346675 ./Music/Raymond-Le/Networked-24hour-alliance/FLAC/01 - None.ogg

294677097 ./Games/PS5/ISO/Exclusive-upward-trending-hub (2014).img

7701455

As such, we need a way of re-assembling the data so it can be processed coherently; this is the main reason I chose a line delimited plaintext format for the index – it makes it easy to split and re-assemble without complicated parsing.

Processing the chunks and re-assembling as they come results in a lot of concurrency – something that async/await really helps with – without it everything could end up looking like a christmas tree.

Here’s the core loop that processes the chunks as they arrive:

| |

Here’s the algorithm:

- Loop until there are no more chunks

- For each chunk, decode it from bytes to text

- Split the text into lines, adding the last partial line from the previous chunk

- Record the last partial line (if any) to be prepended to the next chunk

- Iterate over all complete lines – emitting an event for each line parsed as

<size> <filepath>

The code above is simplified to exclude header parsing. This is achieved like so, within the loop above in reality:

| |

Progress tracking

Despite not knowing how big each chunk will be, we can figure out the progress of the larger index file being downloaded by inspecting the HTTP headers. This, however can be unreliable and depends on correct server configuration; that’s why the index format indicates the size and also file count in the header.

Enabling gzip also complicates things with the meaning or absence various headers.

The progress information is later used to control the progress bar in the UI.

Ensuring the index is compressed

Given the 5x compression ratio I observed earlier, it’s important to make sure the index is actually compressed when served – if it’s not compressed it’s not obvious. Nginx doesn’t gzip by default and it’s easy to think you’ve enabled it when you haven’t.

| |

A check is implemented as above – only for large indexes, and when gzipping has not been declared in the response headers. This is used in the UI to display a banner.

Ensuring the index is current

Another failure that isn’t obvious is when the index is out of date. If files have been added or removed since the index was created, search results will be invalid; that’s why I included a timestamp in the index header.

When the index is loaded, we can compare the timestamp to the current time and warn the user if it’s too old. The UI then displays a banner if this is the case.

This is achieved by inspecting parsed indexAgeMs value in SearchResultsView.svelte:

| |

String matching algorithm

Thanks to the streaming system above, we now have filepaths (known as candidates in the search engine) arriving one by one as they are downloaded. The next step is to match them against the user’s query.

I was quite particular about the search algorithm used here. A good search algorithm will match what the user expects without missing relevant results or including irrelevant results. No algorithm is perfect, but I’ve developed one that works nicely for filepath searching.

If you’re got an even somewhat organised filesystem, chances are you know fragments of the directory names and well as bits of the filename you’re looking for. Therefore, I wanted to match on contextual fragments of the filepath, not just the filename – this is where a lot of search engines fail in my opinion. On to the algorithm!

| |

This algorithm:

- Tokenises the query into words, splitting on non-word characters. This makes the search insensitive to spaces, dashes, underscores and other separators.

- Converts the tokens into lowercase. We do the same to the candidate filepath later to make the search case insensitive.

- Iterate over the tokens, finding the position of each token in the remaining fragment of the filepath – snipping off up to the match each time.

- If at any point a token is not found, return

false. - If the loop completes, return

true.

This works great! The algorithm is also sensitive to the ordering of the words in the query. This works well if you know roughly where the file is located.

Given the index is a list of full filepaths, I needed to somehow match directories containing the files too. Otherwise, if we’re actually matching a directory, we’d get a list of all files within that directory tree!

The way we do this is apply another algorithm I called highestMatch.

| |

This moves up the path, checking we still have a match. The highest matching path is returned. This way, if we match a directory, we get the directory path only. Of course, this requires de-duplication of the results which is handled by the engine. Now, we only show a single directory match instead of all files.

Incremental search

I’ve covered streaming the index and matching candidates against the query, but not how the search updates as the user types.

Also, I haven’t covered how the index is iterated over as a whole even if partially downloaded or searched again with a new query.

The mechanism that triggers the incremental search is straightforward – any time the text input box change, a new search is started.

The key thing here is to stream the index only once. The first search might happen as the index is downloading, but usually subsequent searches will happen when the index is fully downloaded. The search engine handles this splicing by first iterating over the index paths downloaded, then hooking on the events of new paths as they arrive.

Ensuring a smooth UI with web workers

By default, javascript code in the browser is single threaded and blocks UI updates when performing heavy computations. If we were to use the search engine directly, particularly inside Svelte, the whole UI would block until the search is complete. This would defeat the purpose of the idea in the first place!

One way is to effectively schedule. Yield control of the main thread back, allowing the UI to paint. This could be achieved with callbacks – in the browser we don’t have direct control over the event loop. Svelte also exposes some functions like tick() to help with this.

Another solution is to use Web Workers – they allow parallel execution of javascript code in the browser with a few compromises:

- Communication is done via message passing – no shared memory. Data is copied between the main thread and the worker. This is actually a bit annoying, but means that bugs due to shared state are avoided.

- The worker has no access to the DOM – it can’t manipulate the UI directly. Fine in this case.

- The worker must be in a separate file. This complicates bundling somewhat.

I wrote an event-based wrapper around the search engine to run it in a web worker in searchengineworker.ts to handle the state. Unfortunately it makes the code less elegant, but it works.

The worker is loaded as an inlined bundle using vite.js, – this does a horrible thing (loading the script as a base64 data URL) but it means the whole project can be shipped as a single javascript file. See vite.config.ts for how this is done.

Keyboard control

One final feature is keyboard control. I figured as you’re typing to search, why change to the mouse?

The implementation is done twice, once for the search results and once for the directory listing.

| |

The above code keeps track of the selected item via index, updating it (with wraparound) on arrow key presses. When enter is pressed, it simulates a click on the selected item so no special handling is needed.

Conclusion

There’s a lot of wiring not covered here – for instance state updates and other UI code. See the full source code for how it was put together.

Writing the search engine was a fun exercise in balancing trade-offs, and remains in use today with my friends for sharing files quickly and easily. I hope it’s useful to others, and look forward to any code contributions or feedback!

Particularly if you can add any documentation, work on packaging or add meaningful tests I’d appreciate it.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this article or have comments, please consider sharing it on Hacker news, Twitter, Hackaday, Lobste.rs, Reddit and/or LinkedIn.

You can email me with any corrections or feedback.

Tags:

Related: